The walls of Dr. William Schneider’s office are covered with awards highlighting his venerable career at NASA, where he worked for 38 years before becoming a professor at Texas A&M University.

The walls of Dr. William Schneider’s office are covered with awards highlighting his venerable career at NASA, where he worked for 38 years before becoming a professor at Texas A&M University.

Schneider has been a faculty member in the Department of Mechanical Engineering for the past 15 years. His route to Texas A&M started with a phone call from the former head of the NASA space program, Aaron Cohen. Cohen had retired from NASA and was teaching the senior design capstone course in mechanical engineering at Texas A&M.

At the time Schneider was The Senior Engineer at NASA. Cohen thought that he would be well suited for the role and asked if he would be interested in the position.

“I’ve always thought you would be an excellent teacher because you always taught the young people around you at NASA, and they all learned well,” Schneider recalls Cohen saying during their conversation.

Schneider interviewed and took the job and started teaching the senior design capstone project course. Schneider also teaches a number of engineering mechanics courses, including statics and dynamics in the mechanical engineering department.

From Humble Beginnings

Schneider grew up in New Orleans. There was a time in his youth when his life trajectory was slated for a career in the National Guard rather than in engineering. His father thought that he needed 2 years of maturity that the Guard would provide.

“When I was in high school, I was a poor student,” Schneider said. “I wasn’t very motivated.” But Schneider was always fascinated with space. “I always knew since I was 10 that I wanted to be part of the space program. Of course they didn’t have a space program then.”

Everything changed after Schneider switched high schools to Thibodaux College. Schneider became more motivated, played on the football team and started excelling academically. When Louisiana State University (LSU) opened an engineering program in New Orleans, Schneider saw it as an opportunity. Rather than joining the National Guard, he decided to give college a try and attended the university to study mechanical engineering.

One of the professors who inspired Schneider at LSU was from Germany. He taught statics and dynamics. Schneider remembers the first day in the professor’s class.

“Will Mr. Schneider stand up?” Schneider recalls the teacher saying.

When Schneider stood up, the professor continued, “You will be the first in the class, you will be the best in the class. Sit down.”

This moment helped turn things around for Schneider.

“I was first in the class, and it turns out that one of the courses I teach here is statics and dynamics,” Schneider said. “I teach it like him, because he was funny and joking, but he taught the class very well.”

When Schneider was a senior in college, he was introduced to Dr. Maxine Faget, the director of engineering and development at NASA. Faget would eventually become Schneider’s boss and mentor at NASA.

The NASA Days

At NASA Schneider rose to become The Senior Engineer and was one of the six individuals at NASA who could sign off on mission flight readiness. He was also known as the go-to guy for design challenges others found impossible. In one memorable instance, his team designed in six weeks, an inflatable spacecraft for habitat on Mars. This prototype was completed faster than the previous design team and was half the weight.

The inflatable spacecraft went from prototype to reality in 2000, when a billionaire from Las Vegas, Robert Bigelow, wanted to be the first to create hotels in space. Working with Schneider, Bigelow Aerospace successfully launched the first inflatable habitat, Genesis I.

“That inflatable spacecraft, the Genesis 1, is still up there now,” Schneider says.

Genesis II spacecraft was launched in the same year. Both have been in orbit around earth for the past 10 years, weathering micro-meteors and solar flares. They continue to maintain internal pressure, raising the possibility that someday people might live in space.

A New Technology Frontier with Hyperloop

The Hyperloop design competition by SpaceX, is a national and international design challenge which combines advanced aerospace and propulsion technologies. If successful, it could provide an alternative mass transportation mode in addition to airplanes, automobiles and trains. Texas A&M University was selected to host the 2016 SpaceX Hyperloop Pod Competition Design Weekend. On January 29 – 30, 2016, teams from around the country and world will get a chance to present their design concepts in the Memorial Student Center at Texas A&M University.

Conceptually, the design requirement is simple but not necessarily easy: Design a vehicle, “a pod,” that can carry 28 passengers at 760 mph, just below the speed of sound. At this speed, a trip from Los Angeles to San Francisco would take just 30 minutes. This new mode of transportation would be faster than the two-hour flight or the six-hour drive. It could also be less expensive.

The pod travels in a tube with pressure about one hundredth of the pressure outside the window in a commercial airplane flight. This reduces resistance, letting the pod travel faster.

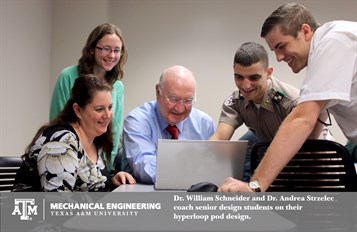

Design teams can comprise of students, engineering professionals, scientists and other interested individuals. Texas A&M also has a formal design course, ENGR 401, Interdisciplinary Design, where students can compete in the Hyperloop competition while fulfilling the requirements for the required senior design capstone course. When Texas A&M University was selected to host the 2016 Hyperloop design competition, Schneider was a natural fit to lead the senior design class of interdisciplinary engineering students. Schneider teaches the course with Dr. Andrea Strzelec, also a professor in mechanical engineering.

“If I had three weeks, me and two other guys could do the whole thing, but our goal is to teach the students,” Schneider said. “They all volunteered to be in this class, so I’m teaching them how to do the needs statement and function structure. Now we are at the point where we are coming with various concepts.”

Preparing Aggies

Schneider’s goal has long been to impart knowledge to engineering students. The Hyperloop competition is a vehicle to impart this knowledge.

“My main goal is to teach the students, secondary is the design competition,” he said.

With 14 patents, Schneider is well qualified to do so.

Schneider is very familiar with the design process. When he was at NASA 20 years ago, charged with the re-design of the Mars inflatable spacecraft. The previous team had designed it out of aluminum so it was very heavy. Although several material choices including graphite-epoxy were suggested to Schneider and his team, he started the design process by asking the question, “What do you want it to do?” Based on the answer to that first question, his team was able to design a successful inflatable spacecraft prototype. Both of which are still in orbit around the earth today.

This design perspective is shared with students in the ENGR 401 Interdisciplinary Design course. The design process for the Hyperloop pod follows the development of a needs statement that guides designers to better understand the problem.

“It is about asking the right questions,” Schneider said, “which allows you to define a needs statement that is a summary of the problem that can easily be explained in a few sentences.”

For Giang Do, a senior electrical engineering student in ENGR 401, the design approach is her biggest takeaway from the class.

“Dr. Schneider says that we will tackle all sorts of designs in our career,” Do said. “The design process allows you to clear out the murky ideas, but it doesn’t limit your creativity.”

At the SpaceX Hyperloop Design Weekend which took place in January, two ENGR 401 design teams will be presented their design concepts along with other teams. Teams which were selected will advance and build their pods and test their design at the SpaceX Hyperloop Test Track in Hawthorne, California during Summer 2016.

“I would want them to see that what we perceive as unattainable is possible. We just limit ourselves based on the little knowledge that we have, or even based on others people’s perception,” Do said.

Classmates Justin Benden, a senior mechanical engineering major and Kenneth McDole, a senior electrical engineering major, believe they were able to represent Texas A&M well and show that the proof of concept is feasible.

“I want A&M to be separated from the other teams, to show that we went above and beyond their expectations,” Benden said. “We didn’t just do what they asked, but rather we came up with our own concepts.”

McDole added, “I want [the concept] to be more of an inspiration for kids in high school and for A&M to be proof that this can happen.”

On Schneider’s wall hangs a picture of him underneath the Space Shuttle Columbia, which he worked on for 7 years at NASA. The picture was taken by Dr. Faget, who recruited him to NASA. It reminds him of the values instilled in him as a young engineer at NASA. These values and the spirit of innovation have not been forgotten by Schneider, and through him, they will be passed on to the next generation of engineers.