When babies are born with complications such as cardiovascular issues that require surgery, their other systems, especially the kidneys, need support. In the neonatal intensive care unit, babies receive this support through peritoneal dialysis, which helps soak up and remove waste through a series of tubes.

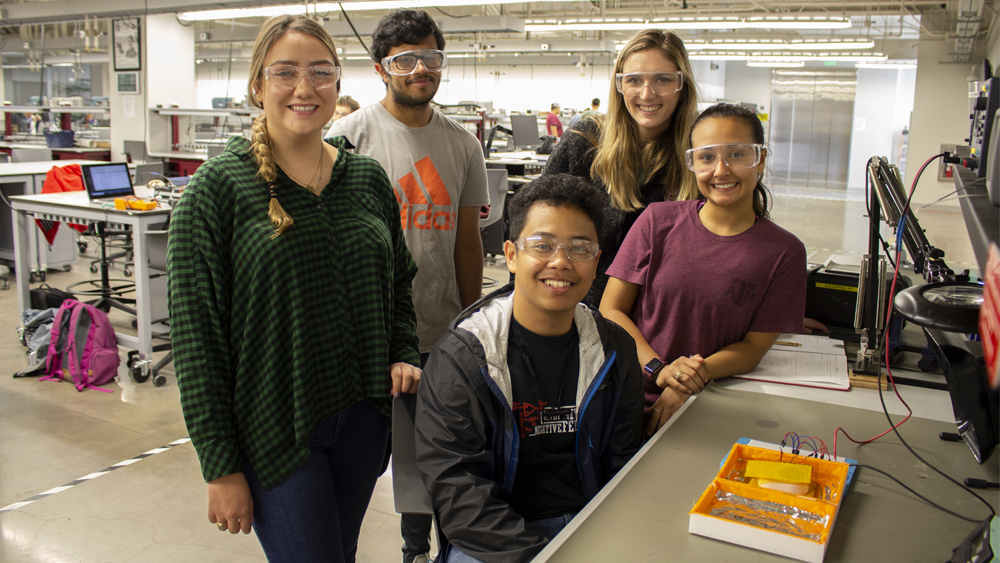

However, this process is currently done by hand, something that a team of five students in the Department of Biomedical Engineering at Texas A&M University aimed to change. The team worked with Texas Children’s Hospital during their senior year to develop an automated system. Nurses who do this procedure manually visit the infant every 45 minutes to complete the process, making it labor-intensive. An automated machine would save time and labor and allow the nurses to act as a second pair of eyes.

“From our research, we haven't found an automated infant peritoneal dialysis machine. Everything has been for ages three and up for automated dialysis,” said Dean Villanueva. “From the research so far, we think it's going to be one of the first automated versions of the infant peritoneal dialysis.”

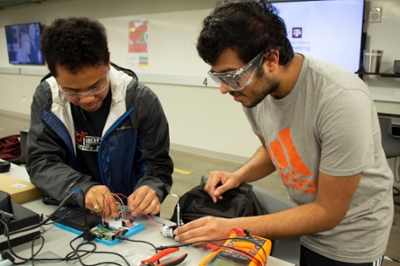

Challenges brought the team back to the drawing board several times, such as temperature control, working with new coding software and making the equipment easy to use. Each time, by assisting each other and playing to their skills, the members came up with innovative solutions.

“There were a lot of components that we didn't know coming into this, how many components that we're going to be manipulating and creating,” said Marissa Heintschel. “I think we've broken it up pretty well between our team, using our strengths and advantages to the best of our abilities.”

“This is the first class where we have full discretion over everything,” said Ashwin Mukund. “A lot of classes have guidelines and, ‘Okay if this goes wrong, you can go to a teacher you can go to someone,’ but this class it’s really all on us to go reach out to whatever we need to reach out on and try to fix our problems ourselves.”

At the end of the two-semester project, the team members reflected on the lessons they had learned. Olivia Moss said the support from their sponsor has been invaluable, not only to help with the project itself but also learning how to communicate with other fields outside of engineering.

“While she can give us answers, it's not the same way an engineer would deliver the answer, so there has been a learning curve,” Moss said. “It's been really good because she cares, and she has really high expectations for us, which has been good.”

Others like Stacy Nuñez discussed how the skills they’ve gained would help them in their future careers.

“I am going into a clinical engineering role where I'll be working with doctors, going into surgeries, etc.,” Nuñez said. “I think it's helped me learn how to work effectively in a group because I'll be working with other engineers and to be able to dynamically talk about problems and solutions.”