The coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic has led to such a stark shortage of personal protective equipment (PPE) that health care professionals have resorted to wearing trash bags as makeshift gowns. Many people have come up with their own unique forms of protective gear to enforce social distancing, from T-shirt masks to shields made out of pool floats.

In hopes of mitigating these obstacles, Texas A&M University researchers Dr. David Staack and Dr. Matt Pharr from the College of Engineering and Dr. Suresh Pillai from the College of Agriculture and Life Sciences began studying ways to recycle PPE through radiation. They teamed up using the Food Technology Facility for Electron Beam and Space Food Research and the Plasma Engineering and Non-Equilibrium Processing laboratory on the Texas A&M campus.

Prior to COVID-19, a large portion of Staack’s research already focused on medical device sterilization and decontamination. Staack, Pillai and Pharr were working on a similar medical device sterilization project funded by the Department of Energy that identified how polymers and plastics are changed when directly exposed to electron beams or gamma rays. So when the pandemic struck, it wasn’t difficult for the research team to shift their focus to begin sterilizing and recycling PPE like surgical masks and gowns, face shields and most importantly, N95 respirators.

There are two components of an N95 mask that determine its functionality: filtration and fit. The N95 mask is composed of microscopic pores meant to filter out contaminants such as dust and fumes down to about 0.3 microns. Combined with an electrostatic charge on the non-woven polypropylene fiber for nanoscale particle trapping, the mask is capable of filtering 95% of particles 300 nanometers in size, if worn properly. Designed to fit snuggly around the nose, face and chin, the mask can prevent germs from escaping through the sides of the mask when speaking or breathing.

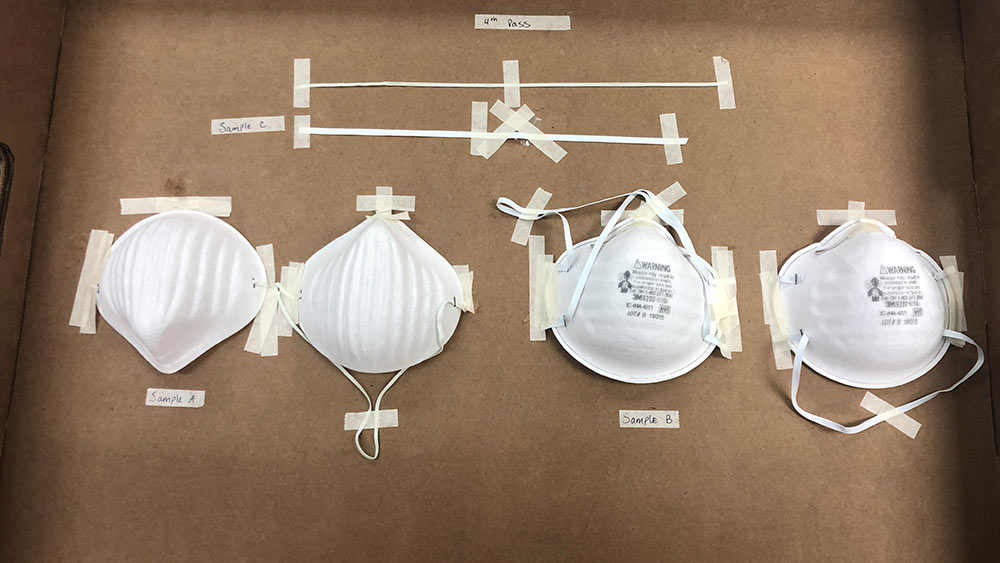

As part of their research, Staack and his team sent brand new N95 masks and other PPE through their radiation recycling process at the Electron Beam Facility. While they found that the mechanical properties of the equipment were not damaged, i.e., the N95 masks, surgical masks, gowns and face shields were all still able to be worn appropriately, the N95 mask no longer filtered 95% of particles.

“The radiated masks ended up going from filtering 95% of particles 300 nanometers in size to only filtering between 50% and 60% of particles a few hundred nanometers in size,” said Staack, the Sallie and Don Davis ’61 Career Development Professor in Mechanical Engineering. “That’s still a lot better than a homemade mask made from a T-shirt.” For perspective, a strand of human hair is approximately 80,000 to 100,000 nanometers in diameter.

Additionally, some of the electrostatic filtration of the N95 mask is lost from a day of wear, hence the disposable nature. And while the first option is to immediately reach for a brand-new mask each day, pandemics like ones caused by COVID-19 can quickly lead to a stark shortage in PPE for health care professionals.

“Of course, ideally, we would want to use brand new PPE, right?” elaborated Staack. “But when that’s not around, what’s the best backup strategy?”

A popular one has been to create homemade masks out of T-shirts, but Dr. Mike Moreno, Dr. John Criscione and Dr. Sarah Brooks at Texas A&M have shown that T-shirt masks only filter about 10% of particles. It also doesn’t conform well to the face, leaving germs and contaminants likely to enter and escape, making recycled PPE a viable second-place strategy.

So, what does PPE recycling look like in the real world?

Ideally, a hospital would box up their used PPE and send it to a radiation facility to be recycled, rather than disposing of them. The Electron Beam Facility is divided in half; one side is designated for contaminated equipment and the other is for clean equipment post-recycling. If the hospital is local, a delivery truck will arrive at the facility’s loading dock on the contaminated side. The boxes of PPE would be loaded onto a conveyer belt moving at three feet per minute and be transported throughout the facility to be radiated. The box passes under a 10-million-electron volt beam and radiates the box with a dose of 25 kilojoules per kilogram –a typical Food and Drug Administration-recommended (FDA) dose for medical device sterilization. This completely sterilizes anything on or within the box by breaking DNA and RNA bonds, preventing any living organism from reproducing. The box then travels to the clean side of the facility, where a new truck transports the treated material back to the hospital it came from and the PPE can be redistributed within the hospital.

Electron beam irradiation is a common, proven and FDA-approved method of medical device sterilization. Irradiation by electron beam, gamma and X-ray methods account for approximately 50% of the market of all medical devices sterilized worldwide. The Electron Beam Facility is already equipped for industrial use, and based on Staack’s research, is able to process and recycle 10,000 masks an hour.

“There’s still some logistical issues we’re working through,” said Staack. “Can we do it safely? Can masks be distributed to someone other than the original user? These are the questions we’re researching now so that if something happens in the short term like another wave of COVID-19, we’re ready. And if something happens in the long term, we’re more knowledgeable about it.”

There are approximately 50 to 100 electron beam facilities in the United States alone. Staack’s goal is to be able to share the team’s results and distribute this critical information around the world so that everyone is better equipped to tackle a global pandemic.