Gulf War Illness (GWI) is a multi-symptom illness that impacts an estimated 25% to 35% of veterans of the Gulf War. Since the war, functional gastrointestinal disorders related to GWI have gone largely unexplained and there are no clear therapies that directly address gastrointestinal dysfunction in GWI.

Dr. Shreya Raghavan, assistant professor in the Department of Biomedical Engineering at Texas A&M University, and her lab aim to develop new ways to research GWI occurrence and treatment options using bioengineering.

“We believe that by investigating the pathobiology of GWI-related gastrointestinal dysfunction, we will be able to therapeutically target it and improve the quality of life of aging Gulf War veterans,” Raghavan said.

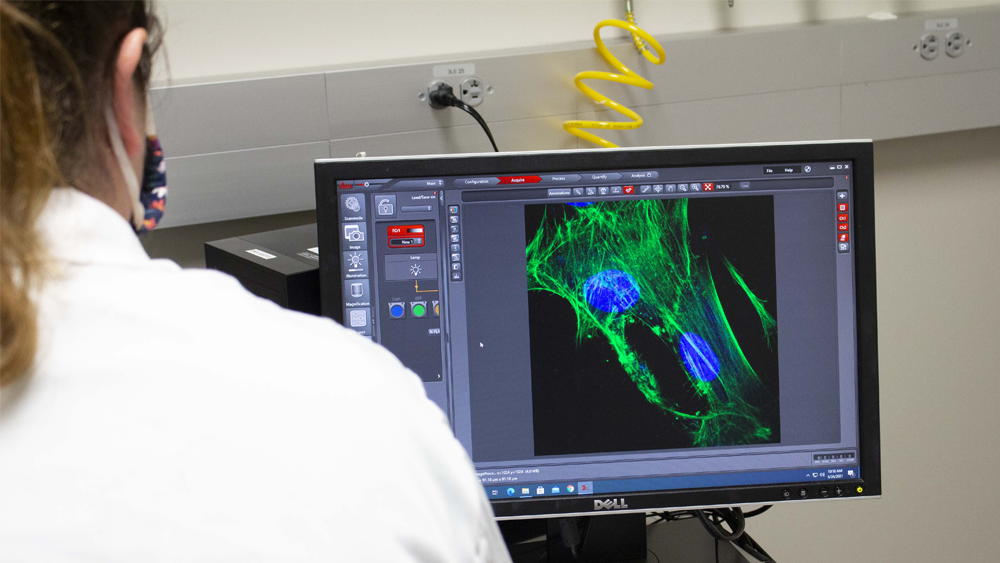

Her lab works on engineering tissue microenvironments for both intestinal inflammation research and cancer. By isolating all the individual cellular components and reengineering them in controlled ratios, the lab is able to better understand the different variables that cause the biological problems. These bioengineered constructs, if made from patient-derived cells, can then be used for personalized, patient-specific treatments.

“The readouts from bioengineered guts/intestines are phenomenally similar to comparable tissues from rodents, rabbits and even humans,” Raghavan said. “Our previous work has shown that by creating these gut structures, we’re able to compare physiological function and show remarkable equivalency.

Raghavan collaborates with Dr. Ashok Shetty, associate director of the Institute for Regenerative Medicine at Texas A&M. Raghavan’s research was recently funded by the Congressionally Directed Medical Research Program through their Gulf War Illness Research Program.

One challenge her overall research faces is sourcing cell material from the patient to form the engineered portion. Many of the issues she’s trying to address impact only parts of the gut.

“For a regenerative medicine approach to work, you have to show that other portions of the gut are still functioning normally,” Raghavan said. “That’s our first challenge — to show that engineered pieces from the uninvolved gut still function physiologically as expected and sourcing enough amounts of autologous tissue to create this solution.”

Raghavan said personal connections have also led to her interest in studying the gut, including family members afflicted with chronic gut disorders. She said engineers are problem solvers, and working as a biomedical engineer allows her to apply her training to diverse biology and medical questions.

“Even outside of GWI, this work has implications in other inflammatory disorders of the gut like Crohn’s and colitis, even cancer initiation,” Raghavan said. “These sorts of personalized medicine approaches are currently not very popular in the gut realm. It will be exciting to generate bioengineered guts, to ask so many different questions like, ‘Why are some patients susceptible to colorectal cancer? Or why do some individuals with inflammatory bowel disorders have disruptions in gut motility, and how can we treat them?’”