The angry, raging waters of the Atlantic Ocean roared up the coastline of Florida during Hurricane Ian in September 2022, leaving behind a wake of destruction. Sailboats were tossed about like toys onto homes and into streets. Houses and businesses were crushed and ripped apart by 150 mph winds, and flood waters surged between 10 and 15 feet high. Bridges were destroyed, cutting access to supplies and emergency services to those who chose to stay behind.

Collecting valuable perishable data — data that are lost once storm clean-up begins — is essential in the immediate aftermath of major natural disasters. Dr. James Kaihatu, professor and division head of environmental, water resources and coastal engineering in the Zachry Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering at Texas A&M University, traveled to Fort Myers and Sanibel Island in Florida in late October 2022. He is a member of the Structural Extreme Events Reconnaissance (StEER) Coastal Hazards Advisory Board, funded by the National Science Foundation.

"The data collected included information on affected structures such as materials of construction, connection and foundation types; damage levels such as percentage of the roof missing and broken windows; and remnants of the hazard on the structure such as high-water marks," he said. "This information is important because it is a direct measure of the impact of the hazard on community infrastructure, but is the first to be lost as a community begins to recover from a disaster."

Extreme storm damage and photos of complete devastation are dramatic and evoke emotion, but from an engineering perspective, these images do not offer information that can be useful for increasing resilience in future events.

"The value is in the 'damage gradients,' the area where the scenario changes from total devastation to a completely undamaged state," Kaihatu said. "It is in these spaces where we can see what worked and didn't."

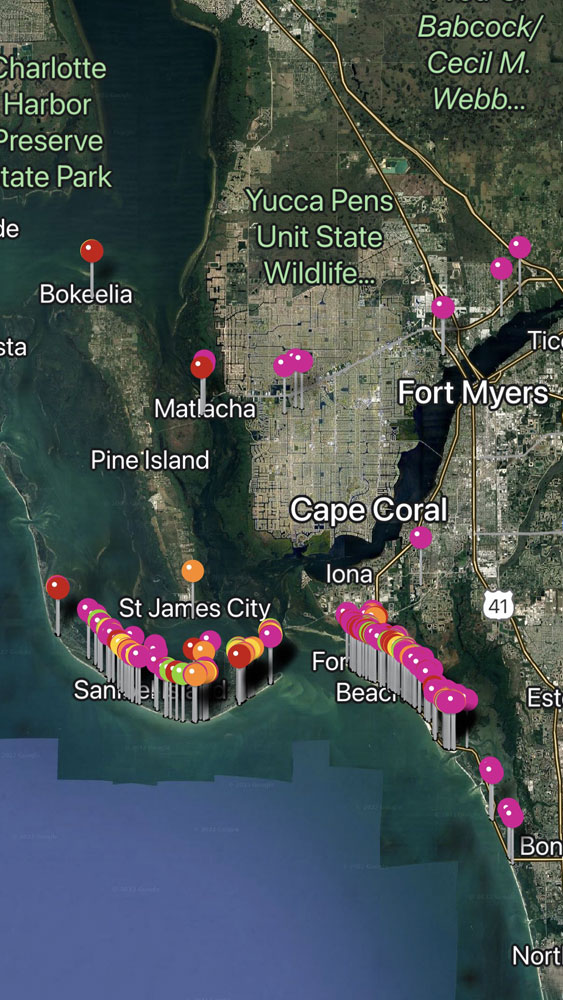

For Hurricane Ian, there were three waves of observers. First, drones and Google Street View cameras took images to assess where a more detailed investigation was needed. The second and third waves, typically structural and coastal engineers, conducted more precise measurements.

"The structural engineers would pre-identify targets in advance, and coastal engineers worked alongside to try to obtain hydrodynamic information (specifically high-water marks) that could lend insight to the causes of failure," he said.

The primary metric to determine floor-related damage is the high-water mark, but the storm surge in and of itself does not necessarily cause structural damage.

"The waves riding on top of the surge have the potential for tremendous damage, particularly if they are impacting the structure as breaking waves," Kaihatu said. "Unfortunately, we currently do not have a foolproof way to determine wave damage."

Both the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration and the National Institute of Standards and Technology were interested in specific types of damage, such as where debris jammed up against buildings and blocked the surge flow or instances where the water flow from storm surge was channeled between two large buildings.

As a StEER member, Kaihatu was in the third wave of observers and began his assessment on Fort Myers Beach, which suffered substantial damage. His team consisted of Dr. Sabarethinam Kameshwar, an assistant professor at Louisiana State University, and two graduate students from the University of Southern California, Behzad Ebrahimi and Maile McCann.

"The shoreline orientation may have played a major role in enhancing the surge relative to other locations, but in addition, many of the houses there were older and lower in elevation," he said. "Some older buildings, which were closer to shore, broke up in the storm and that debris damaged buildings farther inland."

Some preliminary estimates of surge go as high as 16 feet above mean sea level. Most severe damage occurred on the west and central portions of Fort Myers Beach. The east side consists primarily of large condominiums and large belts of vegetation.

"There was some evidence that vegetation played a role in suppressing surge and wave heights," Kaihatu said.

The team traveled to Sanibel Island, where a resident drove them around since access to the island after the storm was limited to residents, first responders and authorized contractors. Sanibel Island's west end was primarily populated with smaller, older structures, and many did not survive the storm. The storm surge in this area and farther east were between 10 and 20 feet above mean sea level. Preliminary results show that the vegetation belt on Sanibel Island reduced the hurricane surge so that areas landward of the belt ended up with 30% less surge elevation than locations on the coast.

This is not the first time Kaihatu has traveled to disaster areas for field reconnaissance. It's his second for StEER and fourth overall. He inspected the damage in Galveston, Bolivar Peninsula, Freeport and Surfside after Hurricane Ike in 2008. Ten years later, in 2018, he traveled to Florida to assess Mexico Beach, Panama City Beach and Port St. Joe after Hurricane Michael. A year later, in 2019, Kaihatu traveled to the Bahamas as part of StEER in the wake of Hurricane Dorian to assess the damage.