Ian Burress is a man of many hats: engineering graduate student, research assistant, student organization president, former wrestler and now sustainability champion.

The Texas A&M University Office of Sustainability awarded Burress the 2024 Sustainability Graduate Student Champion Award for his research on designing a mobile facility that removes per- and polyfluoroalkyl (PFAS) chemicals with little negative environmental impact. The award also recognizes his efforts in reviving the Texas A&M Solar Car Racing Team after a 20-year hiatus.

"It is a wonderful honor to be recognized, especially from a group outside of engineering," he said.

Dr. Velumani Subramaniam, his advisor and an instructional associate professor in mechanical engineering, nominated him during the fall of 2023. "He was able to attend the award ceremony and witness the culmination of two years' hard work, which was nice," said Burress. "It also meant he could see what the future looks like for the solar car team."

Burress is a graduate student in the J. Mike Walker ’66 Department of Mechanical Engineering. He will graduate from the Master of Science in Engineering program.

Forever chemicals

Burress received the sustainability award for his graduate research thesis on designing and simulating a mobile electron beam facility that removes PFAS chemicals. During the last two years, he worked in the Plasma Engineering and Diagnostics Laboratory with Dr. David Staack, his research advisor and associate mechanical engineering professor.

PFAS is a synthetic chemical that renders thousands of products waterproof, stickproof and stain-resistant. We use and even wear most of these items daily, such as clothing, umbrellas, car seats, nonstick pans, medical equipment, outdoor gear and interior furnishings (couches, rugs, textiles).

Also known as 'forever chemicals,' PFAS do not decompose naturally. Their components can last for thousands of years before breaking down. When products containing PFAS are deposited in landfills, the forever chemicals soak into the ground and find their way into water systems, contaminating tap water. Very low doses of forever chemicals have been found to cause health risks, including certain cacogenic illnesses, liver problems and high cholesterol.

On April 19, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency designated PFAS chemicals (PFOA and PFOS) hazardous substances under the superfund law.

"Forever chemicals have been a growing concern for several years," Staack said. "The federal government has worked on understanding the risks and how to protect people properly. The health risks and government mandate associated with these chemicals will continue to be a decades-long conversation."

The Environmental Working Group recently commissioned a study analyzing public data sets of drinking water in the United States. The study involved laboratory tests that found forever chemicals in dozens of cities' drinking water supplies. They estimated that over 200 million people likely receive tap water with a PFAS concentration.

One of the most pressing issues is finding effective and economical ways to separate these chemicals from water supplies and, even more importantly, how to destroy these chemicals. While facilities that break down these chemicals exist, the logistics can be challenging. "If you take chemical-laden soil to a facility, it still has to be transported along roads, and often, those facilities are thousands of miles away," Burress said.

A team of researchers designed a pilot facility to address this concern. Burress brought his background and knowledge of general automotives to the research project. The team designed and built a facility that uses an electron beam to dose the soil. The facility, however, needed to be mobile and compact enough to be transported by conventional shipping methods — such as a semi-truck — that would safely and efficiently move the soil.

The research process involved a lot of hard work, but it felt good knowing that I was creating something practical. It will have a very positive impact in the future and be used to remove something dangerous.

"My first design ended up weighing 40 tons," Burress said. "Something like that can't be pulled on a trailer. I had to go back to the drawing board and figure out, 'Alright, how do I shield this properly?'"

After determining that the final design would take a week to set up, Burress tested the mobile facility for a few days. The result was a transportable facility that workers could set up with relative ease to treat contaminated soil, completely removing any forever chemicals.

"This research proves that electron beam processing is one of the few techniques capable of breaking the carbon-fluorine bond in forever chemicals, and thus remediate contaminated soils, sludges, and waters," Staack said.

The team's research was a collaboration with the National Center for Electron Beam Research at Texas A&M, with funding from the Department of Energy, the EPA and the Department of Defense.

"The research process involved a lot of hard work, but it felt good knowing that I was creating something practical," Burress said. "It will have a very positive impact in the future and be used to remove something dangerous. That helped me stay motivated and keep working on the research."

Cars, solar and beyond

Burress has always loved racing cars. As a child, he learned his colors and numbers through NASCAR. When he isn't completing graduate coursework or researching in a lab, you can find him in a workshop with the Texas A&M Solar Car Racing Team, toiling over their hand-built car.

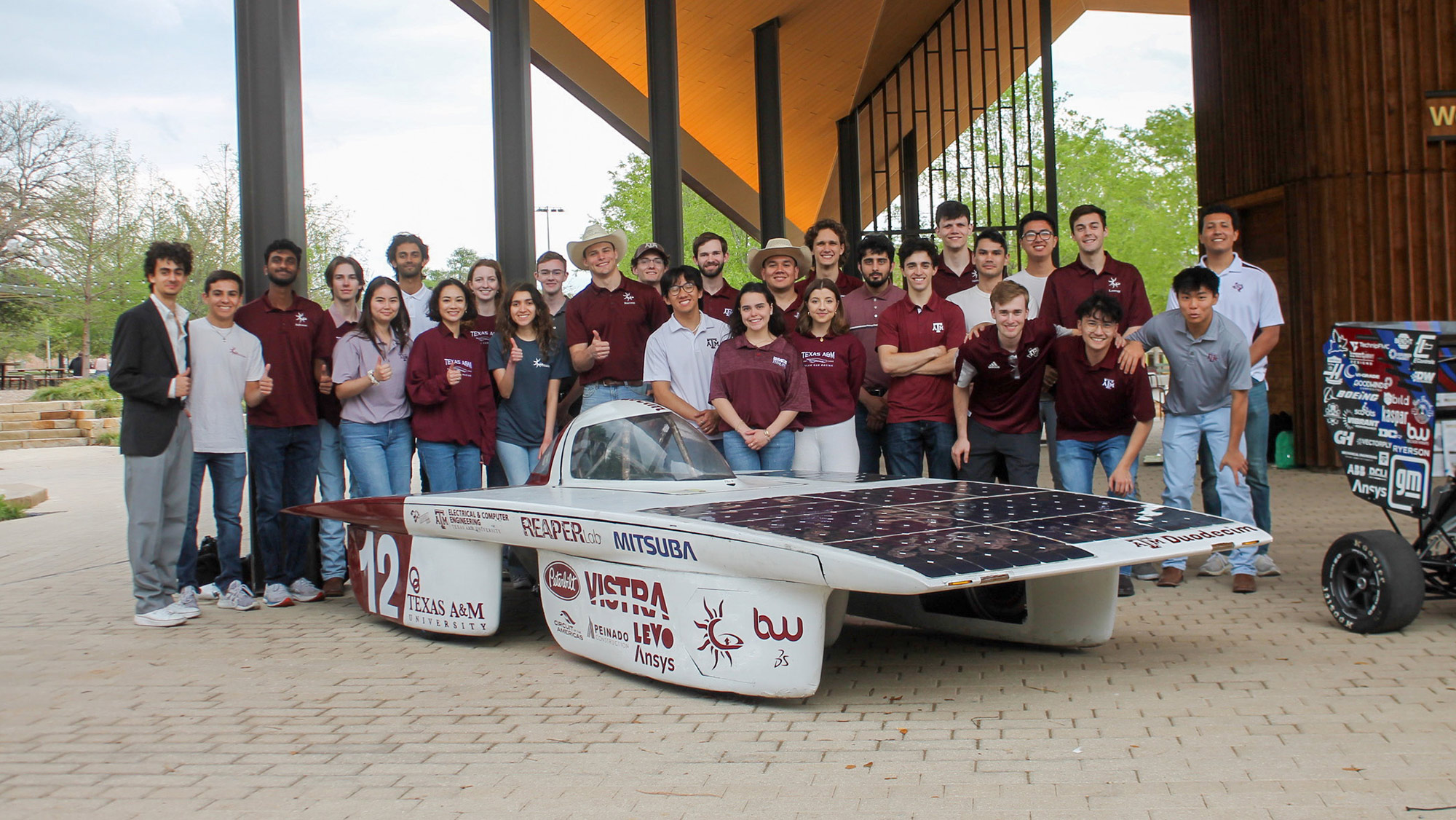

As president and project manager of the team, Burress helps design and race solar-powered battery electric vehicles cross-country on open roads. This summer, the team will compete against over 41 other universities in a lengthy cross-country race beginning July 12.

Burress is uniquely qualified to revive the solar car team. He majored in mechanical engineering at Michigan State University with a focus in automotive power. He was also vice president of their solar racing car team.

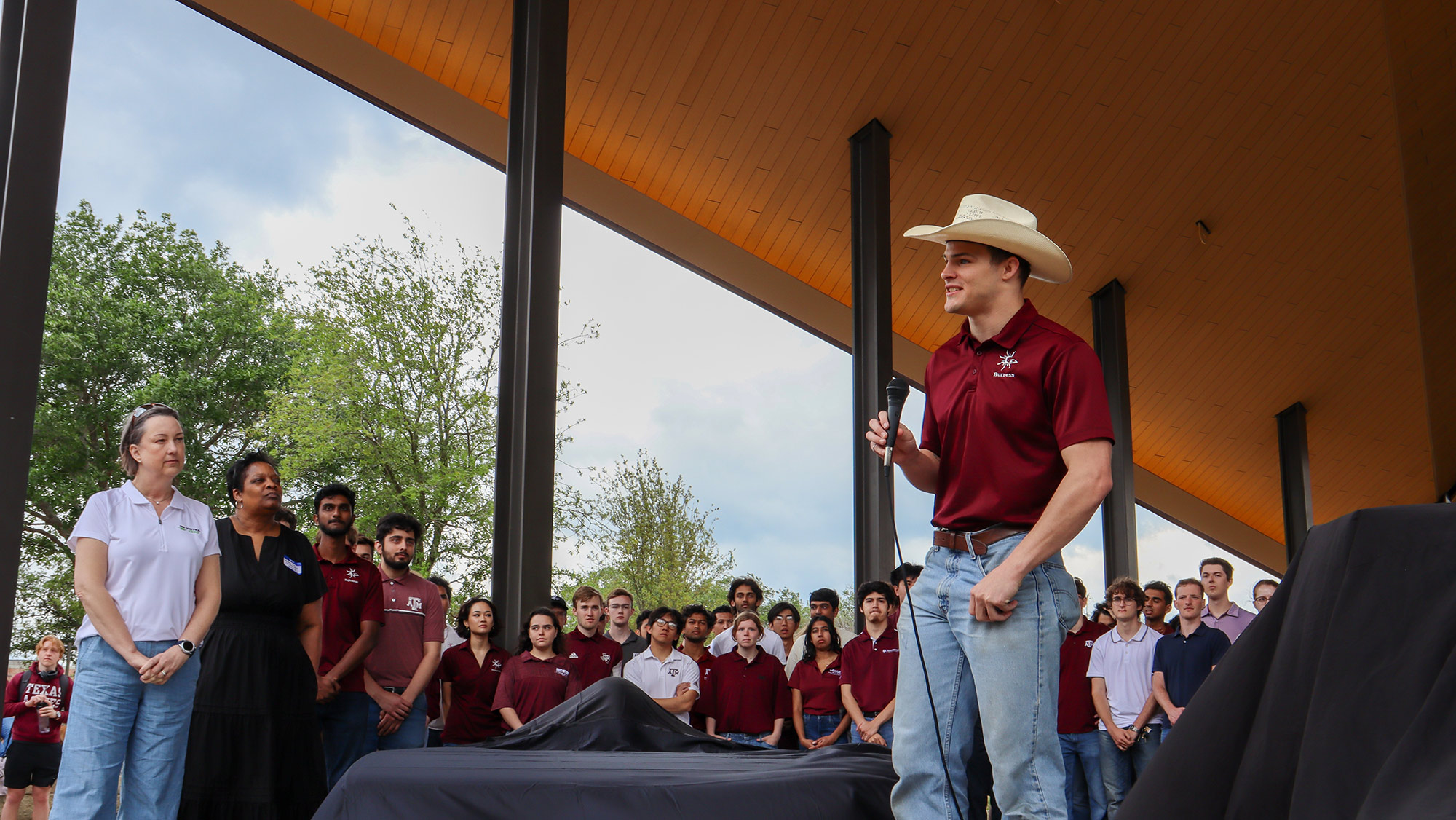

After Burress arrived at Aggieland in July 2022 as a new graduate student, he learned that the department's solar racing car team had been inactive since 2003. He immediately took action. "I knew I wanted to start this team back up, so right then, I began the process," he said. "On the first day of school, I was out on campus trying to recruit for the team. It was just me and our treasurer, talking to any students who would listen."

Two years later, the team counts 80 members on the roster and 60 students on active projects at any time. After this summer’s competition, he will hand off his role to a rising junior.

"I've spent a lot of time developing this team," he said, "so letting them go forward on their own feels special. It will be very emotional to say goodbye. But this is the right time. I feel much more complete in my academic pursuits thanks to the mechanical engineering master's program. My experience has been exactly what I hoped for."

Burress will begin his career as a field service engineer at Caterpillar Inc., where he's previously interned. Burress is also in talks to serve as a potential judge for future racing car competitions. He may even try his hand at a NASCAR short-track race.

"If I don't end up working with cars professionally, I will pursue it as a hobby," he said. "There is always a future in which I am involved in some sort of automotive performance."

As he prepares to graduate this month and reflects on his time at Texas A&M, Burress can be sure of two things. He's leaving a legacy built on passion and can add another hat to his long list of roles — that of an Aggie.