Learning new languages, sending emails, attending a virtual class, or speaking to loved ones halfway around the world are just some of the tasks accomplished by touching a button on a smartphone. Unfortunately, the ease and convenience of modern devices have also come with a painful crick in the neck. The sedentary nature of work and prolonged use of hand-held devices and computers have contributed to a sharp increase in neck pain.

While fatigue in neck muscles has long been suspected of causing pain, the actual mechanical changes in the spine and muscles that precede weakness remain an outstanding question.

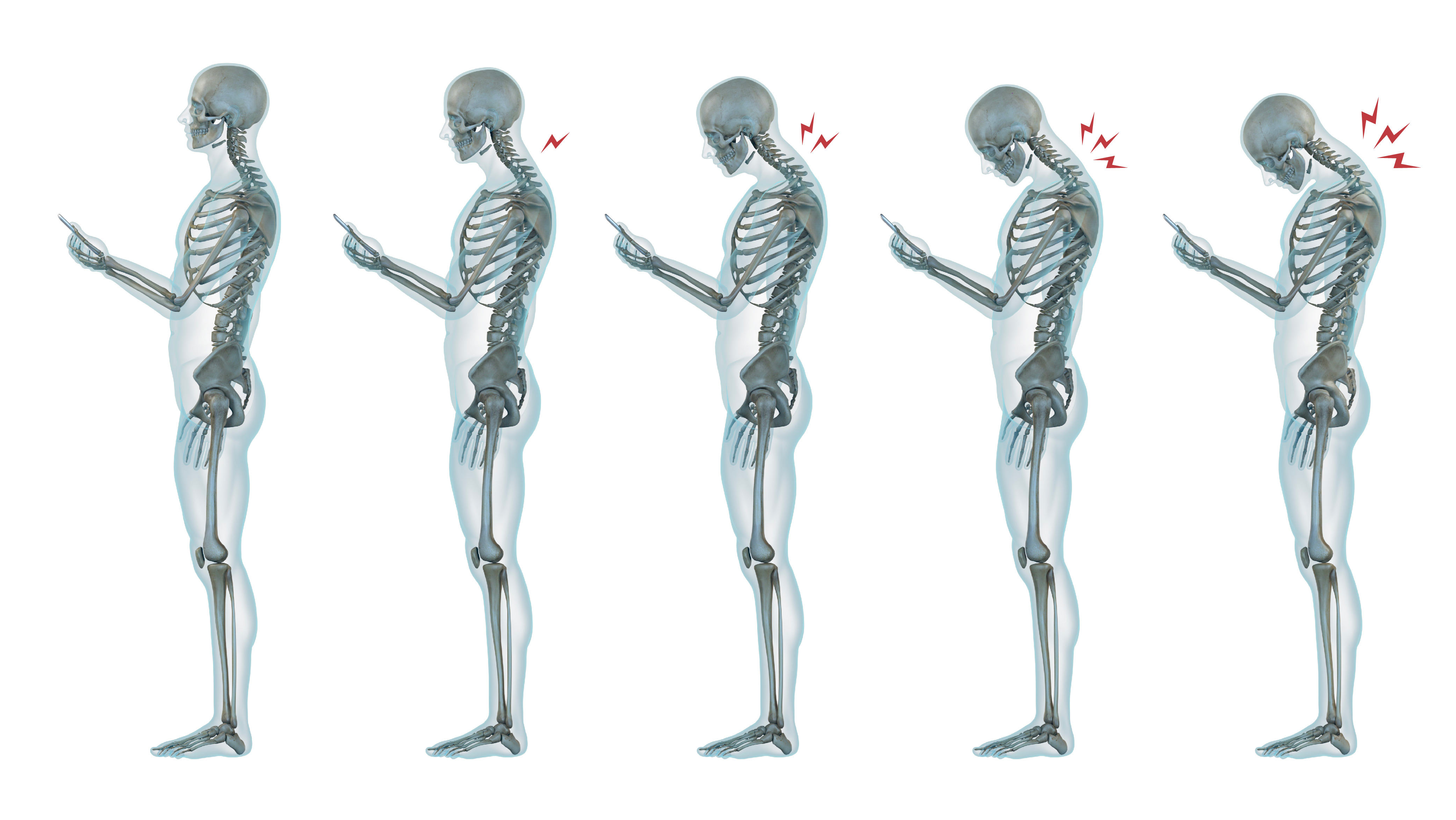

Now, using high-precision X-ray imaging to track spine movements during neck exertion tasks, Texas A&M University researchers have discovered that sustained neck exertions cause muscle fatigue that then exaggerate the cervical spine curvature. This leads to neck pain.

Their results are published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

“We are talking about subtle movements of the neck in statically held positions, which are hard to capture. They are also highly complex because there are so many individual pieces in the neck, or as we call, motion segments,” said Dr. Xudong Zhang, professor in the Department of Industrial & Systems Engineering. “With this study, we have, for the first time, provided unequivocal evidence that fatigue causes mechanical changes that increase the risk.”

Zhang said this understanding can help to make informed decisions about how we work and the design of products (e.g., head-mounted wearables) that can potentially reduce the risk of neck pain.

Neck pain is one of the most common musculoskeletal disorders, and globally, around 2500 people out of 100,000 have some form of neck pain. In fact, by 2050, the estimated global number of neck pain cases is projected to increase by 32.5%. An important risk factor for neck pain is bad posture sustained over long periods. Consequently, working long hours on the computer in a stooped position or prolonged use of smart devices are important contributors to neck pain.

Neck posture is maintained dynamically by the bones of the spine pulled into position by the muscles that attach to them. Although the neck is highly flexible, it is also very unstable.

“The muscle drives movements by producing force,” said Zhang. “We hypothesized that when different muscles’ force production abilities diminish, the bone positions change and that can be captured.”

To test their idea, they recruited healthy volunteers in a “sustained-till-exhaustion” neck exertion task. The subjects maintained their necks in the neutral, 40° extended (bent backwards) and 40° bent forward for a certain duration. The investigators used electromyography (EMG) to measure muscle electrical activity. In particular, they objectively measured muscle fatigue through changes in the frequency of the EMG signal. In addition, they used high-precision, dynamic X-ray technology to track small-amplitude cervical spine movements that were of the order of a few degrees.

“We imagined the cervical spine as a cantilever bridge,” said Zhang. “If there is excessive and/or repeated stress on the bridge, it might sag or buckle; similarly, if the muscles get fatigued, the cervical spine may deflect.”

The researchers’ experimental paradigm validated that sustained exertions indeed lead to EMG signals of fatigue. Biomechanically, the muscular fatigue modified the spine's mechanics, which then increases the propensity for injury.

As a next step, the researchers will develop dynamic biomechanical models, a novel approach that promises to provide a more realistic understanding of the muscular events that precede fatigue. Unlike the model in this study that assumes static neck exertions, the dynamic model will capture subtle but consequential changes in the muscles and bones over time.

Funding for this research is administered by the Texas A&M Engineering Experiment Station (TEES), the official research agency for Texas A&M Engineering.